Freedom often shows up without warning. A flicker of light in the dark, the scrape of a lockpick, a quiet voice saying “follow me”. Rescue stories show up at game tables all the time. They’re not rare, but they’re powerful. There’s something deeply human about them. Most of us have needed help at some point. Most of us have imagined what it would be like to save someone. A prison break, a hostage mission, a race to pull someone out of danger. These adventures work because they get to the heart of drama: someone is in trouble, and time is running out.

But what seems simple is often hiding something more. Beneath the surface, these scenarios are made of moving parts that shift and collide. Each one can spin the story in a new direction.

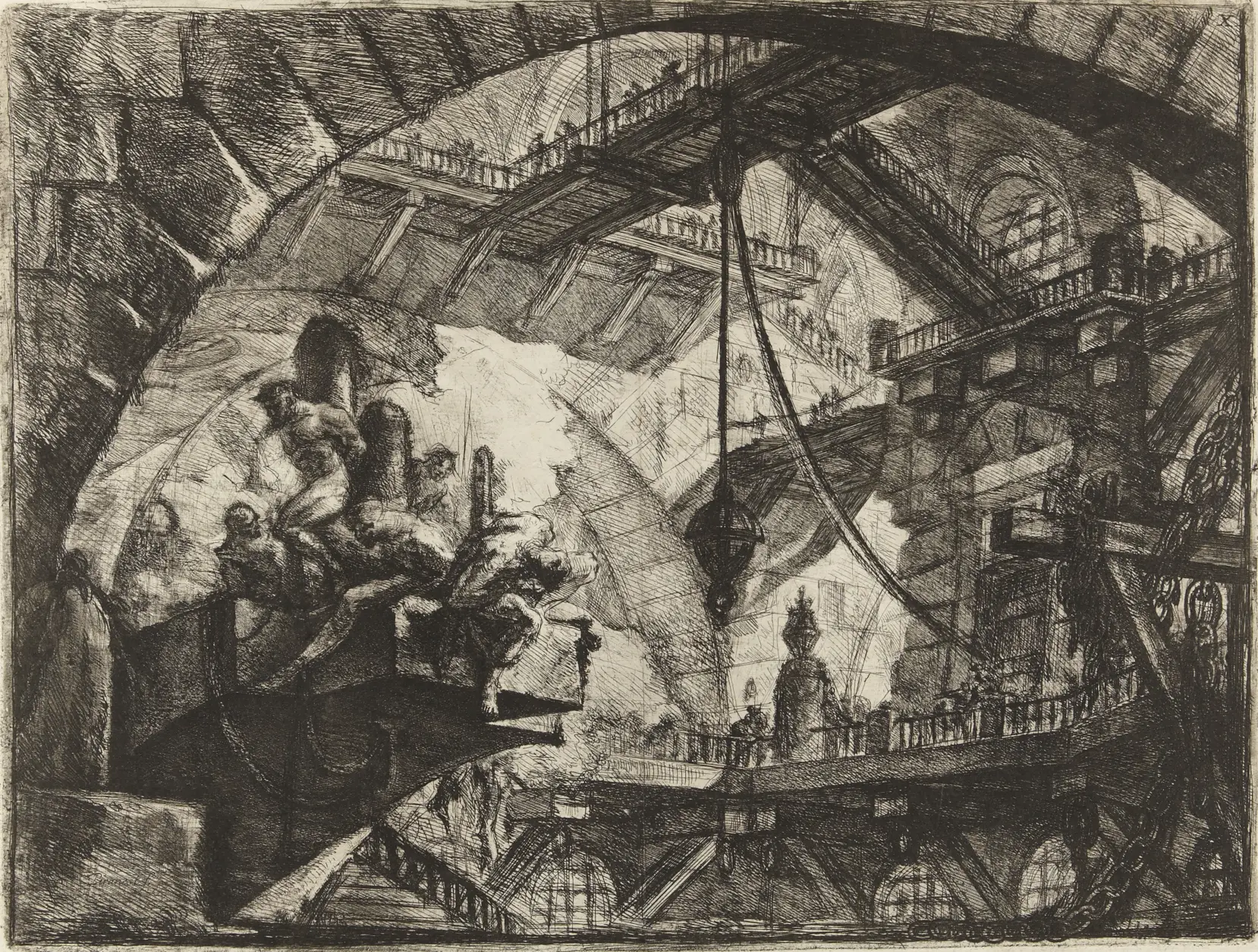

Imaginary Prisons – The Gothic Arch

Let’s begin with a classic setup: bandits, a kidnapped merchant’s son, and a ransom to pay. The solution looks clear. Find the gold, save the boy, punish the bad guys. Simple. And sometimes that’s exactly what your players want.

But then something cracks. Maybe the boy arranged the kidnapping to protect his sister. Maybe the bandits used to work for the merchant and know too much. Maybe the ransom is a distraction, and something else is going on entirely. Every crack in the surface opens up new paths. The story stretches in ways you didn’t expect.

The Geometry of Power

Rescue scenarios are really about power. Who has it, who wants it, and who’s trapped between them.

Power moves through these stories like a current. At first glance, the kidnappers seem to hold all the cards. They use threats and force. The quest-giver seems powerful too, with money and connections. The victim looks powerless. But these first impressions often miss what’s really going on.

In a neon-lit future, the kidnapped AI might be weak on the outside but secretly gathering information, waiting for the right moment to strike. A prisoner might use their situation to build support or leak secrets. Even the person who sends you on the mission might be playing a role. The merchant hiring you might be under pressure themselves. Maybe someone is pulling their strings.

This is where the real structure of the rescue lives. Not in security cameras or locked doors, but in secrets, pressure, and control. When players start to understand this, they’re changing the whole shape of the power game.

Imaginary Prisons – The Pier with Chains

Picture a kidnapped royal heir. It looks simple. Kidnappers use violence. The crown has money and power. The heir is just the victim. But what if the crown is afraid of public failure and can’t risk a bold rescue? What if the kidnappers want political change, not gold? What if the heir planned the whole thing to force the crown’s hand?

At their most fascinating, rescue scenarios are mathematical expressions of power: who holds it, who wants it, who’s caught in the equations between them.

These questions matter because they create real decisions. Once players see the deeper shape of things, they can start choosing. Should they support the heir’s plan, or stay loyal to the crown? Should they protect the whistleblower’s message or get them out safely? The answers change everything.

The Prison as Character

The best prisons in stories feel alive. They’re not simply made of stone and steel. A place where people move through habits, fears, and little routines.

A single guard post can tell a story. One guard always brings coffee. Another hums while walking. The night supervisor gets nervous before performance reviews. None of this is complicated, but it gives your players something real to notice. It turns the map into a place full of chances.

Imaginary Prisons – The Round Tower

stories. Scratches in the wall from games played to pass the time. A loose brick used to trade messages. A vent that carries sound too well. They come from asking what people would really do in a place like this, and following that idea to the end.

The greatest prisons in fiction are living, breathing ecosystems.

It doesn’t have to be a prison. A mansion that holds a political prisoner can grow its own rhythms. Servants whisper about the guest. Guards get lazy. The kitchen staff leaves doors ajar. People change the system just by being in it.

When you build your own settings, focus on these human moments. These little details make your world feel real and give your players something worth watching.

The Moral Calculus of Salvation

Rescue stories ask hard questions. “Save the victim” sounds easy. But time runs short. Not everyone can be helped. Choices start to cut deep.

Say your players pull a gang lieutenant out of danger. That person has information that could destroy a corrupt noble. But helping them also means letting other people down. Should they go for justice, or for peace? One person, or many?

The classic trolley problem becomes real. Save five strangers, or one beloved NPC. The group’s choice leaves scars. They’ll see the results play out in future scenes. Maybe they make a new enemy. Maybe the one they left behind becomes a haunting memory.

Imaginary Prisons – The Sawhorse

Let’s imagine a captured diplomat. Rescuing her could stop a war. Easy enough. But what if her own people set her up to start that war? Or a genius scientist locked away for dangerous work. What if saving her means unleashing something no one should ever see?

Even the way the rescue is done has weight. A full-on assault might succeed but leave chaos behind. A quiet escape might protect the wrong people. What you choose says something about who your group is becoming.

These moments push characters to grow. They’re tests of belief. Sometimes success feels empty. Sometimes failure leaves behind something true.

The Captive’s Choice

The person being rescued often gets treated like baggage. But that’s rarely how real people act. Trapped in a hard place, most of us start to think, plan, and adapt.

A diplomat might have been working for months to earn her captors’ trust. An unplanned rescue could ruin everything. A spy could be gathering intel and needs to stay “captive” a few more days. A holy woman might believe her prison is a gift from the gods and fight against being saved.

Each one has their own view of what rescue means. The story gets deeper when players have to talk not just to the villains, but to the victims too. Then it’s not just a question of getting someone out, but of figuring out what “freedom” even is.

Making It Work at Your Table

All this depth means nothing if it doesn’t fit the game you’re playing. Reveal things slowly. Let players act and discover. Don’t just explain. Show.

They raid the bandit camp and find the merchant’s ledger full of crimes. They break into the prison and find footage of the target turning themselves in. These clues keep the tension going.

Not every mission needs layers. Sometimes a fast, simple rescue is the right call. Use complexity only when it adds something useful.

If the story is about racing the clock, keep the goal simple and clear. If players enjoy solving puzzles, add secrets they can find. If the focus is on relationships, let the emotions and choices take center stage.

Imaginary Prisons – Prisoners on a Projecting Platform

Follow where your story is already going. The goal is obviously not to confuse or to overthink. It is to give your group something that matters. A challenge they want to face. A mission they’ll remember.

Because at the end, how clever your plans were won’t matter that much. What sticks is the moment someone jumped through a window to pull off the save. Or when they realized the person they were “rescuing” didn’t want to leave. Those are the moments worth chasing. That’s what makes it all work.

Leave a Reply