You’re behind your DM screen, watching your players argue about which way to go. Left to the mountains or right through the swamp? They look over the rough map you gave them, questioning the old farmer NPC you’ve been voicing badly for ten minutes. They take this choice seriously, as if it really matters. You smile quietly. You know something they don’t. Whichever way they choose, they’re going to meet the ogre.

You spent three hours building that ogre. He’s got a rusted cleaver and a heartbreaking story about his dead pet pig. You’re proud of this one. So you make the call that every GM eventually makes. No matter the path, they’re meeting him.

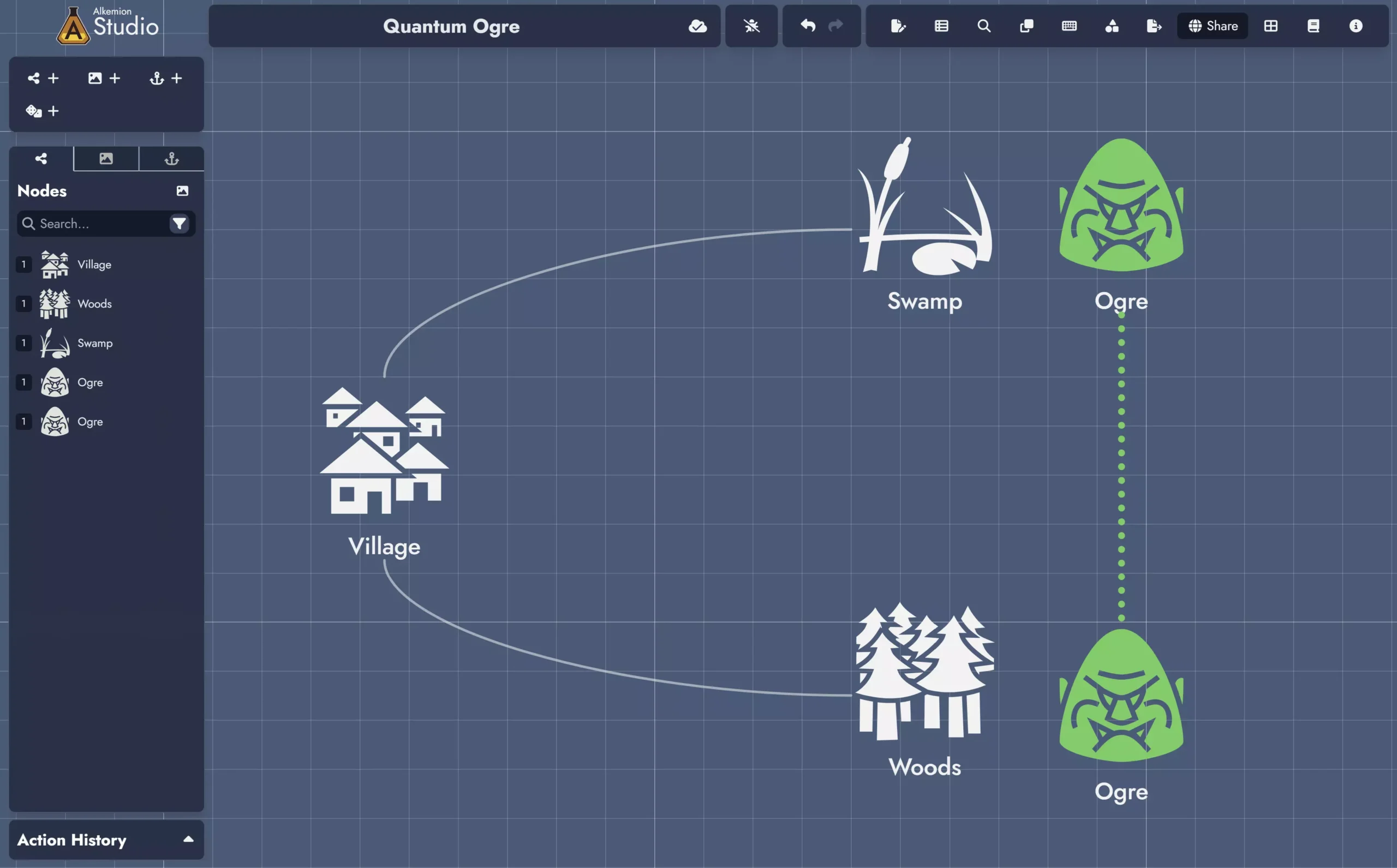

This is the Quantum Ogre. An encounter that’s been placed into the story before your players chose a direction. It floats in a sort of narrative fog, and only settles into one location when the players decide which way to go.

The biggest illusion in roleplaying isn’t magic. It’s choice. And every Quantum Ogre whispers that we’re more afraid of empty space than our players ever are.

The Lie of Choice

The Quantum Ogre is the poster child of a larger trick called “illusionism.” It’s the method of giving players a choice that isn’t a real choice. Like handing a toddler the steering wheel of a toy car and pretending they’re driving.

But what is a real choice? If your players go left or right and meet the same ogre either way, did their choice mean anything? It depends on what we think “choice” is for. Is it about having options, or about those options leading to different results?

Players want their choices to count. Research tells us people value the feeling of control almost as much as actual control. That’s why you press the “close door” button in the elevator even if it doesn’t work. That’s why you throw your own dice.

Players don’t need endless options. They want to feel their decisions change something. It all falls apart when they realize the outcome was already written.

Everyone knows GMs prep things in advance. The players don’t think the ancient temple appeared from thin air. What they do care about is whether sneaking in, pretending to be cultists, or breaking down the front door will lead to different consequences.

So some parts of the game can be fixed. Others should be flexible. When a GM decides too much, the players stop believing they’re helping shape the story. The world starts to feel fake, like a painted backdrop that shifts when they turn around.

And here’s the twist. The Quantum Ogre doesn’t show up because you want control. It shows up because you care. You want them to see something cool. You want to make sure the session isn’t boring. This tension, between great content and real freedom, is the GM’s burden.

The Shortcut That Costs Too Much

Why does the Quantum Ogre keep showing up? It’s not because you’re cruel. It’s because GMing is hard. It takes times to design a good encounter. You gave this ogre a lisp and a glass eye. He’s got clues about the lost temple. You’re not letting that go to waste.

This seems like a fair trade. Until you realize what you’re spending. Every time you drop a Quantum Ogre on the path, you’re cashing in player trust. You’re saving time and effort by selling the one thing they truly value: the idea that their choices matter.

The Quantum Ogre is not a villain. It’s a bargain. And the cost is real, even if no one notices right away.

Players are fine with some direction. They’ll follow your story, if they believe their decisions steer it. When they find out their choices didn’t matter, the trust cracks. Once it breaks, it’s hard to get back.

A good game has both structure and freedom. Think of it like a river. The banks guide the flow, but the water still finds its own way.

The risk comes when the curtain falls. When the players see that every fork leads to the same thing, the spell is broken. They stop investing. They start wondering if anything they do changes the story. That’s the hidden cost of the Quantum Ogre. The price is often paid later.

Mechanics and the Ogre’s Shadow

Different systems handle the Quantum Ogre in different ways. Some ignore it. Some lean into it. Some try to solve the problem a different way.

Game systems are arguments about how choice should work. Some bend the world to the player. Some bend the player to the world.

D&D, especially modern d20 versions, are flexible with the Quantum Ogre. The GM has a lot of authority. Combat is the focus, not narrative freedom. So when the ogre appears, most players don’t care. It fits the vibe.

But in old-school and sandbox games, the rules say the world exists on its own. Players are meant to explore, make plans, and take risks. If the GM moves encounters around to fit the story, it breaks the promise. Here, the Quantum Ogre is cheating.

Narrative games, like those Powered by the Apocalypse, work differently. Some people mock them with terms like “Quantum Bear”, but they’re missing the point. These games don’t plan ahead in the same way. The GM reacts to what happens. The dice and fiction drive the action.

In Dungeon World, you don’t plan an ogre encounter. The story builds itself from how players act. If a monster shows up, it’s because it makes sense. Not because it was waiting offstage. Here, the idea of choice is built into the rules.

Gumshoe takes another route. Clues are guaranteed, not because the game is easy, but because it wants to avoid dead ends. This is a kind of “Quantum Clue,” but everyone knows it’s part of the deal.

So what’s the lesson? The Quantum Ogre isn’t good or bad by itself. It either fits the game or it doesn’t. GMs need to think about what their system expects before pulling it out of the bag.

If You Must Use the Ogre

You love your ogre. Fine. Keep him. But ask first: does he really need to be there?

The best magic isn’t hidden. It’s welcomed. When the players want the trick, they don’t care how it works.

Letting players miss content is powerful. It shows that the world moves with or without them. That their path is theirs.

Still, there are times when the Quantum Ogre makes sense. In a one-shot with limited time. In a game where a specific meeting must happen. Sometimes the king’s messenger will find them, no matter which tavern they enter. It could feel like lazy design, but it’s really a choice made for pacing.

Just don’t make it obvious. If the players go to the mountains, change how the ogre appears. Maybe the terrain influences the fight: narrow cliffs and falling rocks. In the swamp, maybe the water slows movement, and the ogre hides in the mist. Same stats. Different experience.

Or go further. Change the whole encounter. Ask yourself what it’s for. If it’s about combat, put a different monster in each region. If it’s about information, let different creatures reveal it in different ways.

You can even tie the outcome to the choice. The mountain ogre carries a goblin map. The swamp ogre wears a cursed ring. Same encounter. But what players get from it depends on what they picked.

And never break world logic. If the ogre lives in the west, don’t move him east just because the players went that way. It ruins everything. You can say there are multiple ogres. Or maybe the ogre is hunting them. That’s fine. But if it feels like the world is rearranging itself to suit your plans, the spell breaks. The game turns into a play, and the players become the audience.

The Monster Manual Is Uncertain

So how do you keep your prep work and respect player agency?

Justin Alexander’s Three Clue Rule helps. Give three ways to find any important clue. Don’t tie it to one place. Let the players find it in different scenes. They won’t know they missed anything.

Design a challenge instead of designing a monster. Say “this part of the adventure will be a tough fight”. Then let the setting define what that fight is. Wyvern in the mountains, troll in the swamp. Same challenge. Different flavor.

You can also use random tables. Build a list of encounters. Roll when the players travel. The encounter they get is one of many you’ve already planned. This keeps the world unpredictable but fair.

And sometimes the best answer is just being honest. Say, “I built this haunted monastery and I’d love to run it tonight. Would you be okay steering the party that way?” Most players will say yes. They’d rather know than be tricked.

Real power in a game doesn’t come from forcing players to meet the monster, but from letting them avoid it, and making that matter.

Finding the Balance

The Quantum Ogre isn’t your enemy. He’s a tool. Sometimes useful. Sometimes harmful. Always asking questions about what kind of game you want to run.

Don’t ask if it’s good or bad. Ask if it fits. Sometimes it’s worth guiding players to a key scene. Other times, the best session happens when they skip your content and you discover the story together.

Good GMs prepare, but they also stay flexible. They let the world react to choices. They use structure without killing freedom. They plant encounters that can shift without breaking the logic of the world. They create paths with more than one ending. They give out important information in more than one place.

And now and then, they leave the ogre right where they put him. Even if the players never go that way.

That’s when the game becomes real. When the story unfolds not because it was written that way, but because someone made a choice. And that choice mattered.

That’s when the map stops being a stage, and starts becoming a world.

Leave a Reply